When you’re standing on the pier staring up at a modern cruise ship, it’s hard to believe the whole thing doesn’t just tip over. The top decks are stacked with pools, waterslides, and staterooms that look more like high-rise apartments than anything that belongs at sea. It’s natural to wonder: how much of this enormous ship is actually under water, and is that what keeps it safe?

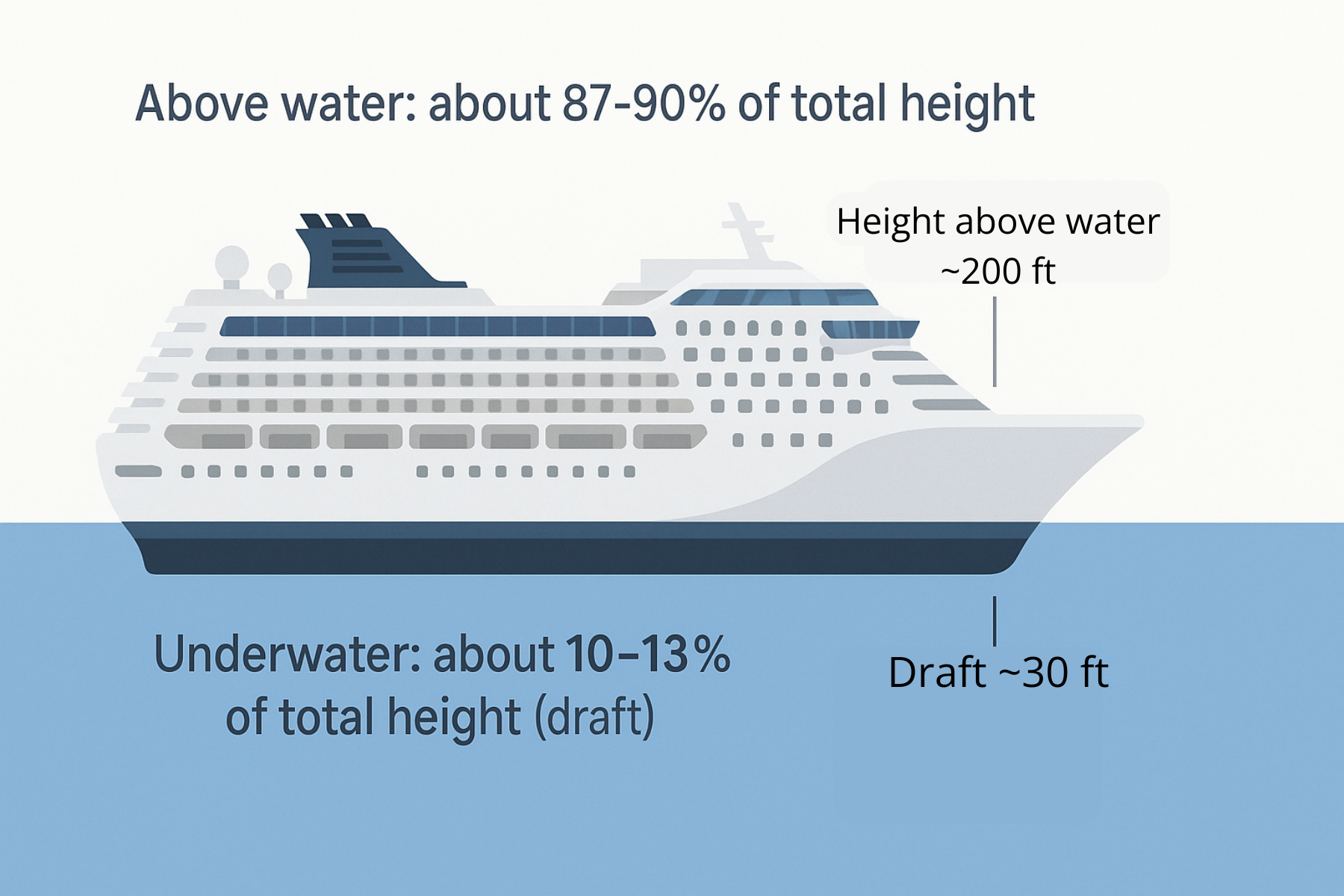

The short answer is that far less of the ship is underwater than most people expect. Even the biggest ships in the world only sit roughly 20 to 32 feet below the surface, depending on their size and design. For example, Royal Caribbean’s new Icon-class ships have a draught (the depth of the hull below the waterline) of about 30 feet, while their total height is around 248 feet from keel to top. That means only about 12% of the ship’s height is underwater.

In this guide, we’ll look at how much of a cruise ship sits below the surface on different classes of ships, what’s actually down there, and why today’s mega-ships can stay remarkably stable even in rough seas.

How Much Of a Cruise Ship Is Under Water? Quick Answer

Most modern cruise ships sit 20–32 feet below the waterline, depending on size.

If you’re more of a “show me the numbers” person, this quick comparison makes it easier to see how much of a cruise ship actually sits under water. These real-world examples (from Icon of the Seas to Queen Mary 2) show typical draft depths and how small a slice of each ship’s total height is hidden below the surface.

| Ship / Category | Approx. Draft (Underwater) | Approx. % of Total Height Underwater |

|---|---|---|

| Large modern cruise ships (general) | 25–31 ft (7.5–9.5 m) | ~10–13% |

| Icon of the Seas | ~30 ft (≈9 m) | ≈12–13% |

| Oasis of the Seas | ~31 ft (≈9.3 m) | ≈11–12% |

| Disney Wish | ~27 ft (≈8.2 m) | ≈11–12% |

| Queen Mary 2 (ocean liner) | ~33 ft (≈10 m) | ≈14% |

The Depth A Cruise Ship Is Under Water (Its Draught)

When we talk about how much of a cruise ship is under water, we’re really talking about its draught (also referred to as “draft”). This is the distance from the very bottom of the hull (the keel) up to the waterline, and it changes slightly from day to day based on how heavily the ship is loaded.

For today’s large, modern cruise ships, the draught is usually around 25–31 feet (about 8–9 meters) when the ship is fully loaded. For example, Royal Caribbean’s Icon-class ships have a draught of about 29 feet (9 m), while Oasis-class ships sit a little deeper at roughly 30–31 feet (around 9.3 m). Quantum-class ships are slightly shallower again, at around 28 feet. Smaller and mid-sized ships often sit a bit higher in the water, but they generally stay in a similar range, so they can use the same major ports.

You might wonder why cruise lines don’t just build ships that sit much deeper in the water to feel “safer.” The main reason is port access. Many popular cruise ports have channels that are dredged to specific depths. If a ship’s draught is too deep, it simply can’t get into those ports or must rely on very specific tide conditions. By keeping the draught in that roughly 25–30 foot band (with the very largest ships edging close to 31 feet), cruise lines can send the same vessels to a wide variety of destinations without constantly worrying about how much water is under the keel.

Instead of going deeper, modern cruise ships go wider. Their hulls are designed with a broad beam (width) and a large underwater footprint, providing the buoyancy and stability they need without requiring an extreme draught. Oasis of the Seas is a classic example: only about 9.3 meters (≈30.5 ft) of the hull is underwater, but the very wide hull helps keep such a tall ship stable without needing a much deeper draft.

Why Such a Tall Ship Can Float (Archimedes in Plain English)

So how does something as big as a cruise ship actually float when most of it is towering above the water? The short answer comes from Archimedes’ principle.

Archimedes was a mathematician, scientist, philosopher, and inventor born in 212 BC and lived in the city of Syracuse in Sicily.

Archimedes’ principle says that an object will float as long as the upward force of the water it pushes aside (buoyancy) is equal to or greater than the weight of the object itself. In other words, a ship floats because it pushes aside (displaces) a huge amount of water, and that water “pushes back” with an equal force.

A cruise ship is designed to make the most of this effect. The hull acts like a giant, hollow metal bowl: it encloses a lot of air and spreads the ship’s weight over a large area. The wider and more voluminous the underwater part of the hull, the more water it displaces and the more buoyant force it can generate. As long as the total weight of the ship, fuel, passengers, luggage, and everything on board is less than the weight of the water it displaces, the ship will float—no matter how tall the decks rise above the surface.

How the Shape of the Hull Helps Cruise Ships Float and Stay Stable

If you look at a modern cruise ship from the side, the part you see above the water can look top-heavy—dozens of decks stacked with cabins, restaurants, and pools. The secret to keeping all of that afloat is the shape of the hull below the waterline.

Cruise ships are designed with a wide, relatively shallow hull. Instead of going very deep, the hull spreads out sideways, giving the ship a large “footprint” in the water. That wide footprint lets the ship displace a huge volume of water without needing an extreme draught. The result is plenty of buoyant force to support all the weight on board, while still allowing the ship to use popular ports that don’t have extremely deep channels.

You’ll also notice that many large ships have a bulbous bow—a rounded “bulb” that sticks out at the front of the hull just below the waterline. That bulb changes how the water flows around the bow, reducing wave-making resistance and improving the ship’s fuel efficiency. It also adds some buoyancy at the front and can help reduce pitching, which contributes to a smoother ride in many sea conditions.

Newer designs, like the parabolic bow on Royal Caribbean’s Icon-class ships, refine this idea even further. The parabolic bow is shaped to improve stability and provide smoother motion in open water, especially when the ship is driving into waves at speed.

All of this works together with where the weight is placed inside the ship. Heavy systems like engines, fuel tanks, and water tanks are kept low in the hull, which helps keep the ship’s center of gravity down near the waterline. A low center of gravity plus a wide hull makes the ship more stable, so it’s much less likely to roll dramatically, even when the decks and superstructure stretch high above the surface.

Does Passenger Weight Change How Deep a Cruise Ship Sits?

It’s easy to imagine that thousands of people boarding a ship would make a big difference in how deep it sits in the water. In reality, passenger weight is a very small part of the ship’s total weight, so it only changes the draught by a tiny amount.

Modern mega-ships like Icon of the Seas can carry up to about 7,600 guests at maximum capacity, with around 2,300 crew members on top of that. Oasis-class ships such as Symphony of the Seas top out around 6,600–6,800 guests, plus roughly 2,000+ crew. Even if you imagine every berth on board filled, the total weight of all the people is still only a small fraction of the ship’s overall displacement, which is on the order of 100,000 metric tons or more for the largest ships.

What does that mean in practical terms? Going from an empty ship to a fully booked sailing will lower the ship in the water, but the change is surprisingly small—typically on the order of an inch or two of additional draught, not several feet. Day to day, you would never notice the difference just by looking at the waterline. From a safety and stability standpoint, cruise ships are designed around the weight of the ship itself, its fuel, water, provisions, machinery, and ballast; passenger weight is already factored into those calculations and does not meaningfully change how safe or stable the vessel is.

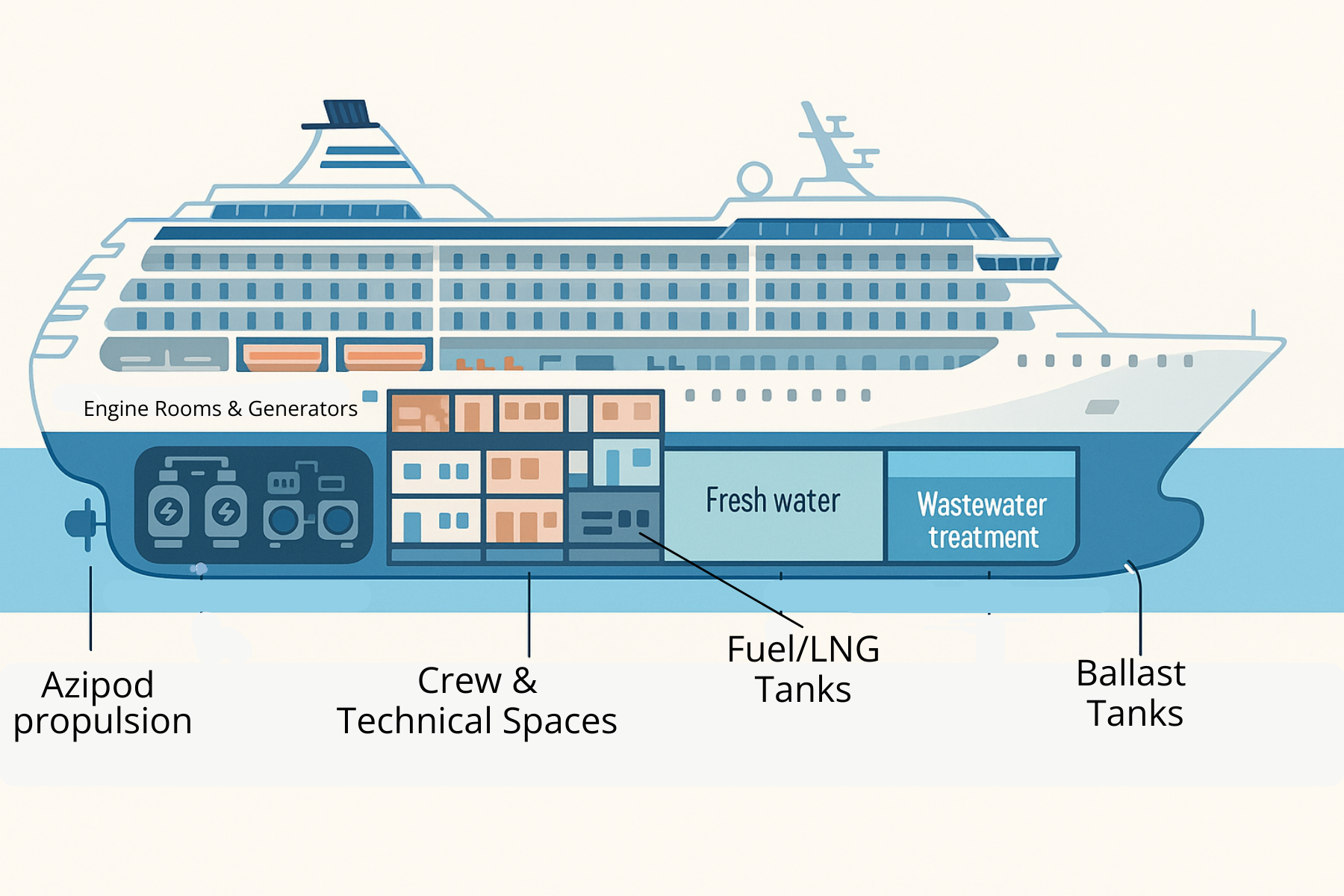

What’s Inside the Part of a Cruise Ship That’s Under Water?

On a modern cruise ship, most of the heavy, behind-the-scenes equipment is tucked deep inside the hull, often at or below the waterline. That’s intentional: keeping the weight low helps the ship stay stable and keeps passenger areas quieter and more comfortable.

Although only a small portion of a cruise ship is underwater, that space is packed with systems that keep the ship stable, powered, and fully self-sustaining at sea. The diagram below highlights the major areas located below the waterline—everything from the engine rooms and Azipod propulsion units to the fuel or LNG tanks, and more. These compartments are designed for safety, redundancy, and efficiency, allowing a ship carrying thousands of people to operate like a floating city.

While the exact layout varies from one ship and class to another, the lower decks typically include:

- Engine rooms and propulsion systems – This is where the main engines and generators live. On many newer ships, the engines drive electric motors that power large, steerable propeller units called Azipods mounted outside the hull at the stern. Those pods can rotate 360°, giving the ship precise control when maneuvering in and out of ports.

- Fuel tanks – Traditional ships carry heavy fuel oil or marine gas oil in large tanks low in the ship. Newer ships—like Disney Wish and some of Carnival’s Excel-class ships—use liquefied natural gas (LNG) stored in heavily protected, insulated tanks in the lower part of the hull. These tanks are designed with multiple safety layers and are carefully segregated from passenger spaces.

- Fresh water and wastewater systems – Cruise ships produce and store huge amounts of fresh water using desalination systems and carry that water in large tanks low in the ship. Separate tanks and treatment plants handle wastewater (from cabins, kitchens, and laundry) before it’s treated and discharged in accordance with environmental regulations.

- Ballast tanks – Along the sides and bottom of the hull are ballast tanks that can be filled with or emptied of seawater. By adjusting the amount of water in these tanks, the ship’s officers can fine-tune the vessel’s trim and stability so it rides level and behaves predictably in different loading and sea conditions.

- Air-conditioning and ventilation equipment – The massive chillers, air handlers, and ductwork that keep the ship cool are largely hidden deep inside the hull and within service spaces, well away from guest cabins and public lounges.

- Crew areas and technical spaces – Many crew cabins, workshops, storage rooms, and laundries are located on the lower decks. Senior officers and some staff may be housed higher up, but a large portion of the working spaces for the crew are below the passenger decks.

Just above these underwater decks, you’ll often find the first fully passenger-accessible level—frequently labeled something like Deck 2 or Deck 3, depending on the ship. That’s where many ships place the main embarkation area, some galleys and storage rooms, and crew dining facilities. The exact deck numbering and layout aren’t universal, but the pattern is the same: heavy machinery and tanks low in the hull, passenger spaces higher up, with service and support areas in between.ats (the mess).

What Stops A Cruise Ship From Sinking?

So what happens if something goes wrong below the waterline—like damage to the hull or a leak? Modern cruise ships are designed with multiple layers of protection to stay afloat and stable even if part of the hull is breached.

Multiple Watertight Compartments

The underwater part of the ship is divided into a series of watertight compartments by strong internal walls called watertight bulkheads. Large doors in these bulkheads can be closed remotely from the bridge or locally by the crew.

If the hull is damaged in one area, water is contained to just a few affected compartments rather than spreading throughout the ship. Cruise ships are required by international rules to be able to survive flooding in specific “damage scenarios”. For example, if any two adjacent compartments are flooded, the ship must still remain afloat and upright enough to keep people safe and allow for evacuation if needed.

Double Hulls and Protected Tanks

Many modern cruise ships also use double-hull construction in key areas. That means there’s an outer shell and an inner shell with space in between. The extra layer gives more protection if the outer skin is scraped or holed, especially around sensitive areas such as fuel tanks and machinery spaces.

If the outer hull is damaged, the inner hull can still keep seawater out, significantly reducing the risk that a single incident will cause severe flooding.

Ballast, Pumps, and Damage Control

Below the waterline, ships have ballast tanks and robust pumping systems that help the crew manage the ship’s trim and respond to flooding. If a compartment takes on water, bilge and ballast pumps can be used to remove water where possible or shift ballast in other tanks to keep the ship on an even keel.

These systems are monitored from the bridge using sensors and control panels that show which spaces are dry, which are flooded, and how the ship is sitting in the water. That gives the officers real-time information to make decisions about speed, course, and any needed emergency response.

Redundant Systems and Modern Safety Standards

Modern cruise ships are also built with a high degree of redundancy—critical systems are duplicated or separated so that a single failure doesn’t put the ship at risk. For example, there may be multiple engine rooms, several independent generators, separate switchboards, and more than one steering and propulsion unit. If one area is damaged or shut down, the ship can often still maneuver using the remaining systems.

All of this is governed by international rules such as the SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea) Convention, which sets detailed requirements for stability, subdivision, fire protection, alarms, evacuation routes, and lifesaving equipment. New ship classes (including the latest mega-ships entering service in the 2020s) are designed and tested against these standards using advanced computer modeling and real-world trials before they ever carry passengers.

None of this makes a cruise ship “unsinkable”—no vessel is—but it does mean that modern cruise ships are engineered to tolerate a significant amount of damage while remaining afloat long enough for the crew to manage the situation and, if necessary, carry out a safe and orderly evacuation.

No Need to Worry About a Repeat of the Titanic

Titanic sank because flooding spread through too many compartments at once and the ship wasn’t designed—or required—to stay afloat with that level of damage. Modern cruise ships are built very differently.

Today’s ships have:

- More and higher watertight bulkheads with remotely closable watertight doors, so flooding can be contained in a limited section of the ship instead of spilling along the length of the hull.

- Double-hull protection in key areas, creating a sacrificial outer skin so that a scrape or glancing blow is less likely to open the inner hull and flood major spaces.

- Redundant systems and damage-control tools such as multiple engine rooms, independent power and steering, ballast tanks, and powerful pumps that help correct list and keep lights and critical systems running while the crew manages an incident.

These features don’t make any ship “unsinkable,” but they make a Titanic-style rapid loss from a single collision far less likely. And unlike in Titanic’s day, modern cruise ships are required to carry enough lifeboats and life rafts for everyone on board.

Why Don’t Cruise Ships Have Underwater Viewing Areas?

On the big mainstream cruise ships that most families sail—Royal Caribbean, Disney Cruise Line, Carnival, Norwegian, MSC, and similar—you won’t find large public lounges or cabins with true underwater windows. Most exterior windows and balcony doors sit above the waterline, and even the lowest passenger decks typically have portholes just at or slightly above the surface, not down in the deep.

That said, there are a few niche exceptions in the expedition and ultra-luxury world that sometimes show up in social media photos:

- Ponant’s Explorer-class ships (such as Le Lapérouse, Le Champlain, Le Bougainville, Le Dumont d’Urville, Le Bellot, and Le Jacques Cartier) feature the Blue Eye underwater lounge. It’s built into the hull a few feet below the waterline and offers views through large, curved “eye-shaped” windows, along with sound and light effects that let guests see and hear the underwater environment.

- A small number of older or specialty ships have experimented with underwater observation rooms in the past (for example, the former Seabourn Pride class once had a “Nautilus Room” with underwater viewing windows), but these are rare and not a standard feature on modern family-focused ships.

For the typical Caribbean, Bahamas, or Mediterranean family cruise, your “close to the water” experiences will come from promenade decks, low outdoor decks, tender platforms, and water-level lounges and bars, not from being literally underwater.

If your kids are picturing a full glass tunnel through the ocean like an aquarium, that’s not something today’s mass-market cruise ships offer—but you can still get excellent sea views, and in some ports you may have the option to book submarine or semi-submersible excursions if you want a true below-the-surface experience.

Closing Thoughts

Cruise ships are truly feats of engineering. How much of a cruise ship sits underwater ranges from 20 to 31 feet, depending on the size of the vessel. However, the safety and stability of a cruise ship aren’t due to the depth that it’s submerged, but rather a combination of factors such as the shape of the hull.

If you are fascinated by cruise ship facts, you may also enjoy this post.